The power of deep listening: insights from Emily Kasriel’s new book and our research

Summary: This week, BBC journalist and a long-time More in Common friend, Emily Kasriel, is coming out with a book on her pioneering method for high-quality listening: Deep Listening: Transform Your Relationships with Family, Friends, and Foes. More in Common contributed original research to the book, which we discuss here, followed by a personal reflection from the lead researcher, Calista Small.

Do you think you are a good listener? If so, consider yourself in good company: according to More in Common’s research, nearly 8 in 10 Americans think they are “good at listening.”

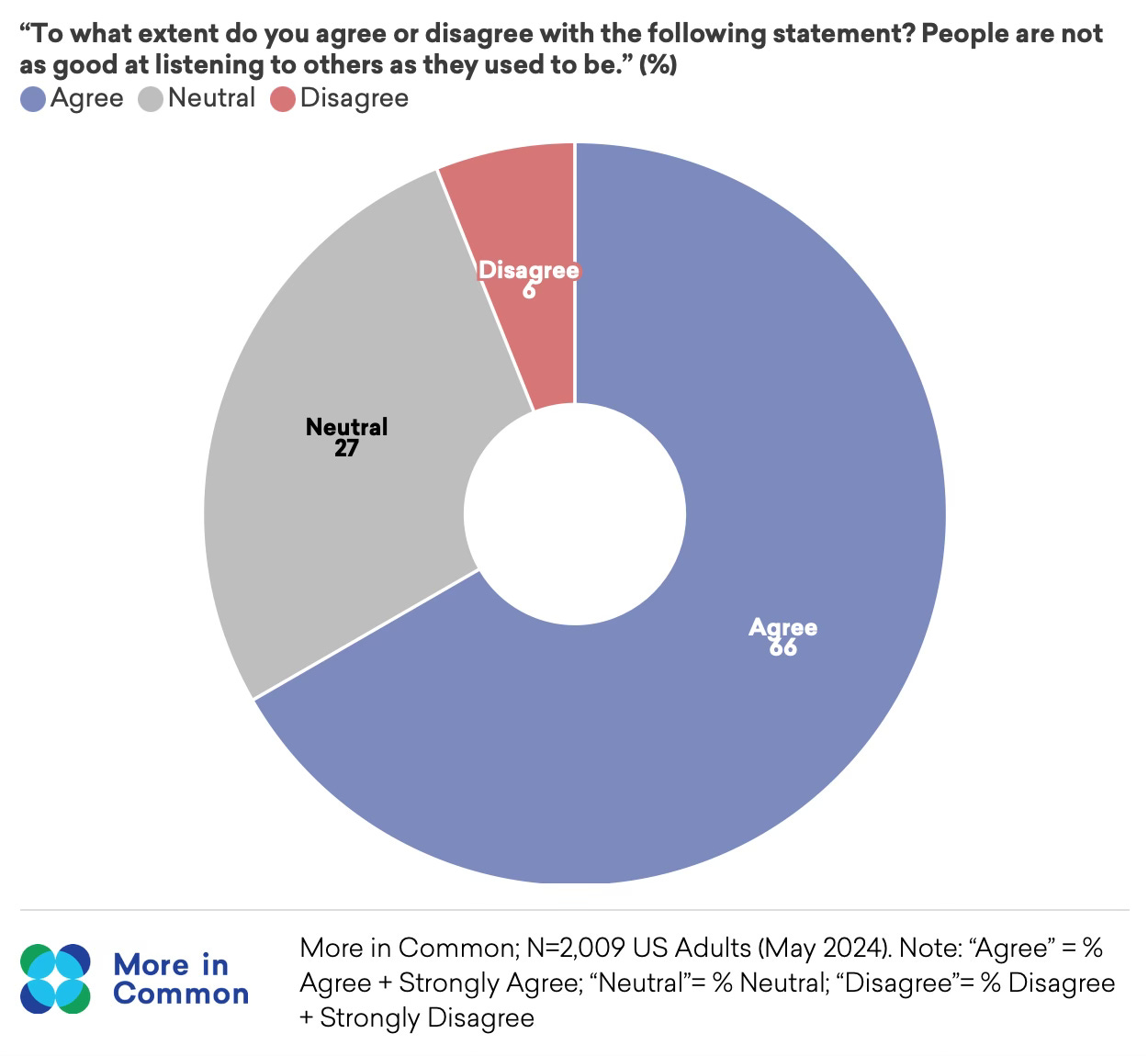

Now: do you think other people are good at listening? If you have doubts, you’re also in the majority: according to our research, around two-thirds of Americans believe that “people aren’t as good a listening as they used to be.”

This discrepancy reveals an important gap between our self-assessment and perceived reality. While somewhat amusing, it also points towards an underlying problem: many Americans feel as though people aren’t listening well these days.

Not listening to each other has important consequences. Feeling unheard could contribute to the lack of connection and loneliness that afflict many. Our data show that it also relates to feelings of belonging: 40 percent of people who feel “excluded” in their local community think that “no one really listens to them” — twice the national average. Broadly, it’s also important for people to listen to each other so that we can understand each other better and thus be able to productively work together in a pluralistic society.

One promising solution to equipping Americans to be better listeners is what Emily Kasriel calls “deep listening.”

What exactly is high-quality or “deep” listening?

As Emily Kasriel details in her book, high-quality or “deep” listening goes beyond everyday conversational listening. It requires the cultivation of both a specific skill-set and mind-set.

As a skill-set, deep listening involves indicating to the speaker that you are paying close attention to what they are saying: having open body language, making eye contact, and then paraphrasing back to the speaker what you heard.

As a mind-set, it involves cultivating an unjudgmental approach to the speaker: slowing down internal thoughts to devote attention to what the speaker is saying, and trying to understand the speaker’s underlying values.

Some might fear that listening to someone with opposing views might make the speaker think that they agree with them, which could lead to a hesitation to engage. However, this assumption is mistaken. Deep listening isn’t about showing agreement so much as respect, which is critical for connection.

Why does deep listening matter?

One reason deep listening matters is that it can help people better connect, especially with those who are different from themselves. This is because deep listening can make individuals feel more confident in navigating potential tensions or misunderstandings, thereby reducing any potential anxiety about the interaction.

Deep listening benefits the speaker in a conversation, too: it can make speakers feel respected and understood, which are essential conditions for mutual trust and connection.

What do Americans think it takes to be a good listener?

As mentioned earlier, many Americans think they already are good listeners. So, are they interested in developing high-quality listening skills? And do they see listening as important?

We find that two-thirds of Americans believe that people don’t listen as well these days. And while 8 in 10 think they are good listeners, many are willing to improve: a significant number of Americans (48 percent) express a desire for opportunities to learn how to listen more effectively.

Remarkably, when we ask Americans to describe what “good listening” looked like, they provide clear – and consistent – definitions:

They look at you in your eyes while you are talking, they may nod their head in agreement. You can also watch for their body language. They may also provide feedback to what you have said.

Shaney, Baby Boomer, liberal Black woman

They are looking at you and really focusing and responding to what you are saying. They are not on their phone or looking distracted.

Sheila, Gen Z, conservative white woman

They don't interrupt or try to change the subject. They ask thoughtful questions during the conversation, reacting in the moment, not jumping in with advice. Listening more than they speak. They don't judge [and] may rephrase or summarize your conversation.

Art, Baby Boomer, moderate white man

Americans' shared interest in (and understanding of) listening points to a powerful opening: a public appetite for skill-building that can directly support efforts to bridge divides and foster stronger, more empathetic connections.

A personal reflection

When I was younger, I would constantly argue with my close family members about politics. These arguments would become emotional, and, ultimately, unproductive. Afterwards, we’d apologize to each other but then privately double-down on our opinions.

Over time, these experiences made me feel disconnected to the people who raised me, and I longed for a solution.

Every year, around Thanksgiving, there seemed to be a flurry of opinion articles about how to “talk about politics with your aunt over turkey,” and I read all of them. But the recommendations were superficial, and while they could have helped smooth over a hot topic for a few hours, they certainly weren’t enough to sustain me for the rest of my life. I needed something more.

After learning about deep listening a few years ago, I started applying it to my conversations with my family members. My relationships are now stronger than ever. Recently, even, a close relative who I used to bicker with every holiday made an incredibly meaningful request: if I could be an overseer of his trust. While we still disagree, we now have a deeper, more authentic understanding of one another — a shift that Emily Kasriel correctly identifies in the title of her book as “transformational.”

Learn More

Read a free summary of Emily Kasriel’s “eight steps” for deep listening here.

Read Emily Kasriel’s book, which can be purchased here.

Learn about More in Common’s contribution to the book here.

We can’t do this without you!

MIC regularly conducts research that sheds light on both cross-group misperceptions and common ground. Consider supporting our work by making a donation.