Jay's Notes: Q+A on the German Elections with Laura Krause, Executive Director of More in Common Germany (Part 1)

Summary: Jay’s Notes is a weekly (ish) space where our Executive Director, Jason Mangone, can sling his takes.

One of the blessings of working at More in Common is having embarrassingly intelligent colleagues in several different countries. We’re in the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Poland, and Brazil – with a mini office in Spain, too. Each of More in Common’s country offices focuses most of their efforts on their specific country context. But when the opportunity arises, it’s helpful to take a comparative approach. With that in mind, last week’s German elections gave me a great excuse to try out my first Q+A on this channel.

Laura Krause is the Executive Director of More in Common Germany. She also spent a lot of time in the US—including her junior year of high school as an exchange student, and most recently in a fellowship at Yale. The first time I met Laura in person, I immediately noticed that she was able to express sarcasm that was poignant, funny, and relevant to an American context. That’s a very hard thing to do in your second language!

This Q+A will be released in two parts, with this week’s focused on the elections that just happened, and next week’s focused on the way ahead.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

So, Germany is a country in Europe. Most Americans know that. You also had an election over the weekend. Maybe like 5% of Americans know that. So, given that baseline of knowledge, can you just explain what happened over the weekend in Germany and just give us a general understanding of the situation?

Yes. So on Sunday, we elected the next German parliament, the Deutsche Bundestag, which we do about every four years. And now we did it a bit earlier than originally planned. We did it after three and a half years, and we can talk about why we did that.

So in essence, this is what happened. We voted for about 600 new parliamentarians, and now they have to enter coalition talks to form a coalition. And a majority in the parliament will then elect our new chancellor.

Got it. And why was this election held after three and a half years, as opposed to four years?

Because we had a coalition the last three and a half years – that was the first time that we ever had a three-party coalition at the federal level. Essentially, for the past few decades, we've always had coalitions, because no party ever has more than 50%. But those were always two-party coalitions. And because of the diminished size of the parties we, for the first time, had a three-party coalition.

We called it the traffic light coalition, because it was Social Democrats (red), Green Party (green), and the Liberal Party FDD (yellow). And this coalition had been in a lot of trouble, because the war in Ukraine started two months after they came into office. And so all the plans were essentially out the window that they had made and where they had found common ground.

And so after about a year of pretty open infighting, and a lot of conflict, and just what felt to a lot of Germans like a stalled government, it finally broke apart in November – a day after the US election.

And so can you just talk a little bit about the results of this weekend’s election? What the voting results were, and also what the process is going to be to form your new governing coalition – and who the likely next chancellor is.

So election night was a bit of a nail biter. Not because it was a close race between who would come in first or second or third place, that was quite obvious.

And I will talk about that in a second, but we have a 5% threshold for parties to even enter the German parliament. There were two parties that were just at that limit. So what happened is that the Conservative Party won the election with about 28% of the votes. That had been expected for months, the polls showed that it was quite obvious that would happen.

The AfD, which is a far-right party in Germany, came in second. And this is the first time in a federal election in Germany that the AfD that has been around for, which is about 10 years, where it came in second with about 20% of the votes.

And the Social Democrats, who are the oldest Social Democratic Party in Europe, a really old German party, they came in third with 16%. Which for them, is a huge loss. They lost almost 10% of the vote. And then the Green Party, that was also part of the last coalition, came in at 12% – but will likely not be part of the next government.

And then, as I mentioned, there were sort of three parties where we were not sure whether they would make it in—the Left Party called Die Linke, or “ the left.” They had a huge sort of campaign in the last couple of weeks, actually, they were set to be dead, but got 9% of the vote.

And the Liberal Party is not only out of the government, but out of the parliament for the next four years. So is the BSW, which is a newly formed party that broke away from the Left Party with their lead figure, Sahra Wagenknecht. And the BSW did not manage to make it into the parliament, even though they were expected to.

So we had a few surprises, but we will have a five party parliament with a very strong AFD. What does that mean moving forward? All democratic parties had vowed to not enter coalitions with the AfD, because the AfD is considered anti-constitutional in a lot of German states. But because they have a big chunk of the vote, there needs to be a government. It's not that easy to build a government without them.

There's one coalition that is possible with two parties, which are the Conservatives and the Social Democrats. Which we used to call this a grand coalition in Germany. They have a majority of about eight seats, and those two parties will now enter informal talks already at the end of this week. We'll sort of carve out what the process could look like for coalition talks that will probably start mid-March and will run probably for at least a month.

So, to recap: five parties are going to be a part of the new government, if we were going from left to right on the farthest left are Die Linke and the Green Party, which form a small part of the government.

In the middle of the five parties with seats is the Social Democrats. They came in third. They're going to form a coalition with the conservative party, the center-right Christian Democrats, who won the plurality of seats with about 28% of the vote. So that party’s leader, Friedrich Merz, is going to be Germany’s next Chancellor. The Christian Democrats and Social Democrats comprise just over 50% of your parliament, or Bundestag. And to their right is the AfD, which has about 20% of the seats.

I want to talk a little bit more about the coalition, but obviously the big news is the rise of the AfD. Can you just talk a little bit about their rise and how they gained so much prominence? When did they get started? How has their vote share grown over time?

So the AfD, which stands for Alternative for Germany, was actually formed as a business or as a fiscal policy party. It was formed during the Euro crisis by a bunch of professors who didn't agree with Germany's and Angela Merkel's course in the Euro crisis. They essentially also called for Germany to leave the EU. So that's sort of where they originated.

All of those figures left the party relatively quickly. By now, all of them have left, because in around 2015 and 2016, they really became a migration policy focused party – a xenophobic party in many regards, and started to run on those issues. The AfD has sort of gone up and down in support ever since then.

So basically, for the last 10 years, they've had state elections. They even had 14% of the vote eight years ago, also in West Germany. So it's not that they came out of nowhere. But what has sort of been foreshadowing this result that we have now (i.e. where they came in second) was last year, when they ran a very strong campaign around the European elections. And they had a very strong showing at three East German state elections where in one of them, they came in first for the first time.

The AfD has a stronger support base in East Germany. There are many reasons for that. One of them is that traditional German parties have weaker roots in East Germany, because they weren't around before the fall of the Berlin Wall. There are fewer traditional party bonds where people say, “Oh, my family has always voted this way or that way.” In East Germany, every party is a new one over the last 35 years.

But of course, there are many other things that feed into the AfD support. Many people feel overlooked in East Germany or more disenchanted, and the economic situation there is weaker than in other parts of the country.

I think what's really important for the US context is that the AfD is not a conservative party or just a more conservative party. The AfD is a party that has been officially labeled by the German domestic intelligence service as certified right-wing extremist in many states, which is a long process. It takes years, and it has to be proven. There's evidence that they – their members or their party leaders – are a threat to the German constitution and to the German democratic order. And they have that status in three states. They don't yet have it at the federal level, but they're monitored for that.

I think that in the American context it’s quite odd, right? Because why could a party be unconstitutional? But Germany actually has a mechanism for banning parties that was introduced as a learning from the Second World War and from the Weimar Republic.

The fact that other parties don't want to enter a coalition with the AFD isn't just party strategy, or that they don't like their policies. It's really that there is evidence that they're not strongly rooted on the grounds of the German constitution, and they have very strong ties to Russia and a lot of scandals around party finances. So that in combination, we could do a whole podcast, about this. But I think this is really important to keep in mind, especially as figures like Elon Musk got really engaged with supporting the AfD. They’re not just a party. They're a pretty unique party in German postwar history.

Thank you. Now, let me break down a couple of stereotypes about what Americans are saying about the AfD. The first is that all the explanatory power for the rise of the AfD is mass migration into Germany when Angela Merkel accepted, you know, a million plus Syrian refugees in the country, and you've had, you know, massive immigration inflows since then.

The idea is that this policy shift ensured that eventually there would be a rise of a populist far right party in Germany. To what extent is that true? And to what extent is that not true?

The narrative that you're describing from the US is also one that's quite prevalent in the German media. It says that this whole election campaign the last couple of months really just focused on migration, or essentially about crimes committed by migrants.

But actually, when we look into the data and research, it's not true that migration is the main driver of the AfD. What's going on is the long, growing disenchantment with political representation, with political parties, with the feeling of being overlooked. And when we did focus groups recently on this, people say “Look, I tried the other parties. They didn't fix the problems of the country, and I'm going to try this one now.”

And there's a desire, which I think the US can relate to, for big change. Not for things to sort of chug along as they have been. Not incremental change, but big change and disruption. That said, I will send you the chart later, because I don't know the exact percentage but the majority (65%) of Germans don't want the AfD in government.

So we're still sort of in this phase where people vote for them partially because they completely agree with their platform, and partly because they know it's the best way to send a signal. That's really important moving forward, to read those signals well, to listen. Not to just think it's about migration, but to actually look deeper. Because actually German migration policy has changed quite significantly in recent years. It's far away from where it was during the Merkel times.

Germany has gotten a lot more restrictive. And I think that's sort of lost in the public conversation. And we know from our data that Germans primarily care that their state, that the government, has control over who's coming and how many are coming. So it's a different desire.

So you’ve said that there's a desire for change, and so a vote for the AfD is often a protest vote, or a signal to “The Man,” as we would call it in the US, that “I'm not satisfied with what's happening in my country.”

When your fellow Germans feel that they are not heard, what is it that they feel unheard about, in addition to immigration?

It's a general sense, and I think we see this coming up in other countries too, that Germany is on the decline. People are very worried about the power of the German economy. It’s one of the things we're most proud of – the German economy. Or we used to be. And people really say that we're on the decline.

Our infrastructure is crumbling. The German trains are not on time anymore. There are all these things going on, and they have a deep, deep, deep disenchantment. With the most recent government, it’s also around green transition and energy prices increasing, etc. So that is mostly the unheard part.

People say, “Who's going to fix the problems of this country? When? Who's really going to have the common sense to do and to move forward, you know, and to really bring the country back?” And so migration is an aspect of that. But it is not at the heart of what we hear in focus groups, or when we talk to people. So there's – I would say that this immigration-centered narrative did not really represent what people actually were worried about the most.

You quickly touched on the former East Germany and their voting habits. A map that's been going around in the US is the map showing the voter breakdown regionally in Germany. All of East Germany is colored blue AfD. The rest of Germany is not, I'm sure you've seen this map.

You already alluded to this a little, but one story that you could tell from that map is “Well, of course, that used to be in the Soviet sphere of influence, and so people there feel more at ease voting for a party that has strong ties with Russia.”

But what you indicated is that it has more to do with the fact that the former East Germany has only been a part of the new German democratic system for 35 years, and so they don't have deep familial and community affiliations with any one party. So it might just be more that their votes are up for grabs.

Whatever the actual answer is, it's much more interesting than just, “Oh, they're more easily influenced by the Russians.” So, can you unpack this a bit more? What's the explanatory power of that geographical voting pattern, if there is one?

What you're describing is a debate that has been ongoing in Germany for a long time: whether people in East Germany just vote differently and are now less inclined to democracy, or whether that comes from its past.

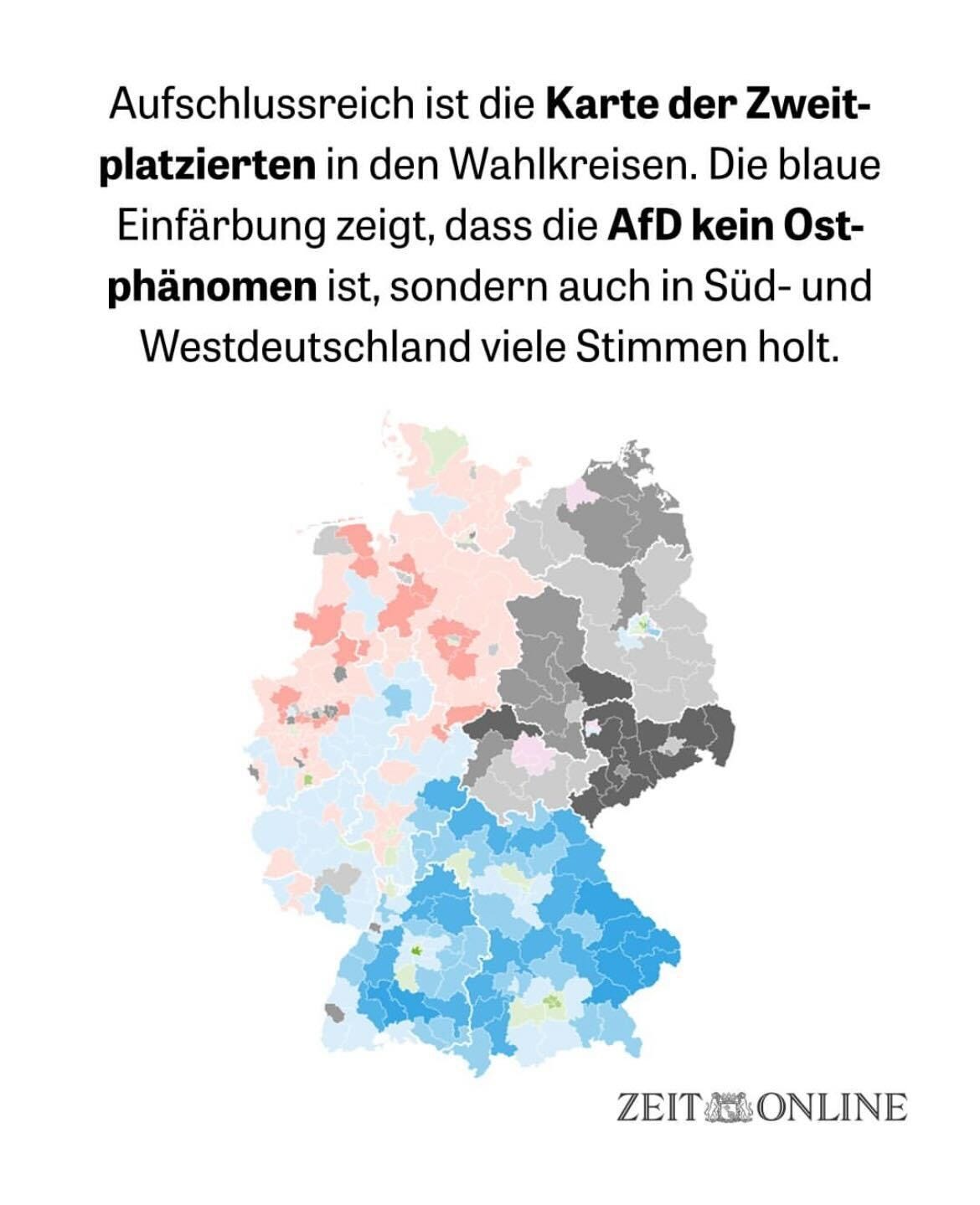

But what we've really been pushing at More in Common is to look a bit more nuanced and deeper at what's going on, because I just sent you another map that shows who's in second place across Germany, and it shows two things.

First of all, the AfD is not just an East German phenomenon. This is a conversation that a lot of people in Germany love to have, because it pushes the responsibility to a part of the country that they are not a part of.

And what we saw in this election is that actually in southern Germany, the conservative sister party or CSU (which is the Bavarian conservatives) has been very strong. They can often govern without a coalition partner. They're a very strong party down in the south. So the southern part of Germany is blue in this map because the AfD comes in second place in southern Germany.

So I think it's important to look at the dynamics that are going on around East Germany. And for example, the whole state of Thuringia has fewer party members for the Social Democrats than there might be in an entire West German city. All of Thuringia has 4,000 party members, whereas a city like Dortmund or Duesseldorf will have the same amount of people just in that city. So it's just that people have organized themselves differently.

People tell us that in East Germany, you know, it was a lot about who you know and who you trust in your community, because that's what you had to rely on in that system. There's more questioning the state and the media from your personal experience, you know, because you grew up in a system that had controlled state media and just one party. So, of course, there are different strands going on.

But I would really caution everybody against thinking it's just an East German phenomenon. We treat East Germany as a laboratory at More in Common Germany, because we say what's happening in East Germany could well happen elsewhere. The party bonds are declining in the rest of Germany too – younger people don't enter parties anymore. They prefer other forms of activism or other forms of community engagement.

So things that happen in a small state in East Germany, they could easily happen in another area of Germany as well, and we are starting to see that as well. I've seen the map. I've seen very many similar maps, but I think it's important to look at both sides.

We need to really look at what are the structural things where East Germany really is disadvantaged. For example, there are way less businesses in East Germany than the rest of Germany, for historic reasons. But we cannot fall into the trap of just pushing the problem to one area, because more than half of people in East Germany did not vote for the AfD. You know, they voted for other parties, and those people are often overlooked themselves.

So moving a little bit to the future. Did the Christian Democrats do anything to stave off the growth of the AfD in advance of the election? In other words, have they adopted any policies, positions or messages meant to be responsive to the AfD’s growth?

The spirit of this question is not mere political positioning. I think something that More in Common does really well, is trying to begin from a place of “We are in a democracy. 20% of my fellow citizens have voted for a party that I might disagree with, but I take their positions seriously, and I want to understand them deeply.” So I want to understand the ways in which the AfD’s rise may have forced the center right to be a bit more responsive to growing dissent within Germany.

Yeah, I think it's a common misperception here, or just in general, a common misperception that the AfD as a political force hasn't had influence. The opposite is true. The AfD’s narratives and platform have been very visible in German politics in the last year, and, I would say, even longer. A key area where this has played out in this campaign is that the Conservatives originally planned to run an economy-focused election campaign, because the German economy is in trouble, and that was mostly what their platform was about. But because we had a few really horrific attacks in Germany, the AfD jumped on that.

In essence, the Conservatives stopped talking about the economy and they only talked about migration. And that's a direct result of trying to react to the AfD and trying to sort of pull away voters. What we see in sort of the voter movement is that this didn't work. The opposite happened. The Conservatives took on a very, very, very right political position on migration, but they lost votes to the AfD and so they were not able to pull people back from the AfD.

So I think this is the big conversation now for conservative parties, especially in Europe. We have seen this in other countries where conservative parties have sort of tried to shield themselves by adopting policies, for example, mostly on migration getting tougher. And it never worked for them. Look at the French conservatives. They don't really exist anymore. You know, the Austrian conservatives are under continuous pressure because they have a very big party similar to the AfD.

So, I think this is the big crossroads where the Conservative Party in Germany will stand now in the next two years. The AfD, and this is important to note, openly says that they want to “destroy the Conservative Party.” They say that in these words. And so I think this is the interesting conversation. So in a way, they have pushed them already.

And parts of the Conservative Party, of course, really agree with this platform as well, and didn't like what Angela Merkel did. But I think it's a big strategic dilemma for the Conservatives that they will have to sort of grapple with now that they're going to be in the Chancellery.

Part 2 coming next week, with a focus on the future of Germany.

We can’t do this without you!

MIC regularly conducts research that sheds light on both cross-group misperceptions and common ground. Consider supporting our work by making a donation.