Jay's Notes: Getting a Good Deal out of American Leadership

Jay’s Notes is a weekly (ish) space where our Executive Director, Jason Mangone, can sling his takes.

Two weeks on from the Oval Office blowup between Presidents Trump and Zelenskyy, I find myself wondering if the meeting was just another of the bombastic, but mostly inconsequential, dustups of which there have been far too many to remember in the last ten years; or if it’s a moment that will be seared in my memory as the indelible signal that the postwar security order is coming to an end after 80 years.

If I’m looking for it, I can find evidence in support of either conclusion. In the last two days, the United States has re-entered direct negotiations with Ukraine over a minerals deal, Ukraine has agreed to a cease fire, the US has restarted security assistance and intelligence sharing, and when asked if President Zelenskyy would be welcomed back in the White House, President Trump replied, “Sure, absolutely.” On the other hand, President Macron summarized the sentiment of Europe when he referred to the US stance toward Ukraine and Russia as a signal of “irreversible changes” in an address to the French public last week—an address in which he floated the idea of extending the French nuclear umbrella to protect the entire continent.

It's taken me about 200 words to say: I have no idea as of yet how to make meaning out of what happened in the Oval Office two weeks ago. I looked at the cross-country polling about Ukraine that we released on Monday, and some associated qualitative work on our Americans in Conversation panel, in search of something that felt enduring.

What I found was a tension that seems likely to animate foreign policy debates in the US for years to come. Americans value their country’s role as a global leader and symbol of democracy, but unlike in the recent past, they are quite conscious of the resources it takes to lead globally. They’re unsure if American global leadership, as President Trump might put it, “is a good deal.”

Americans Uniformly Support Ukraine

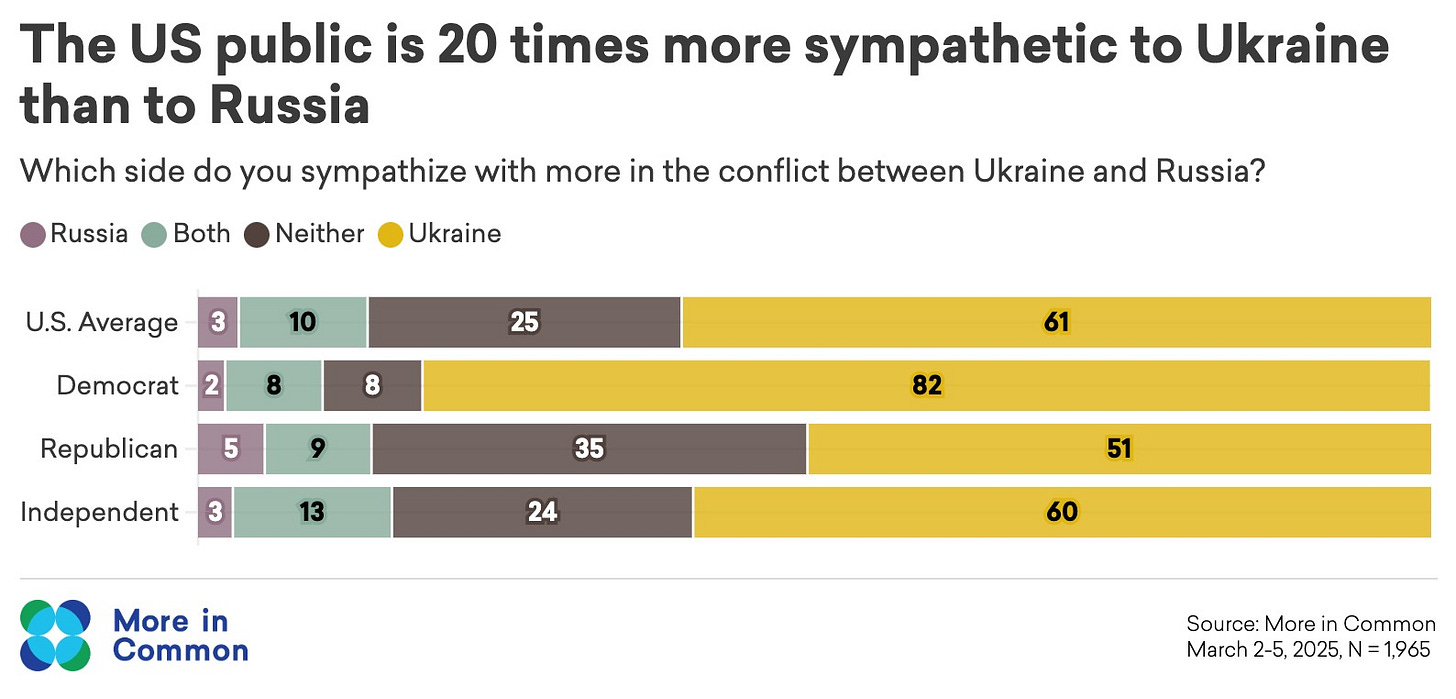

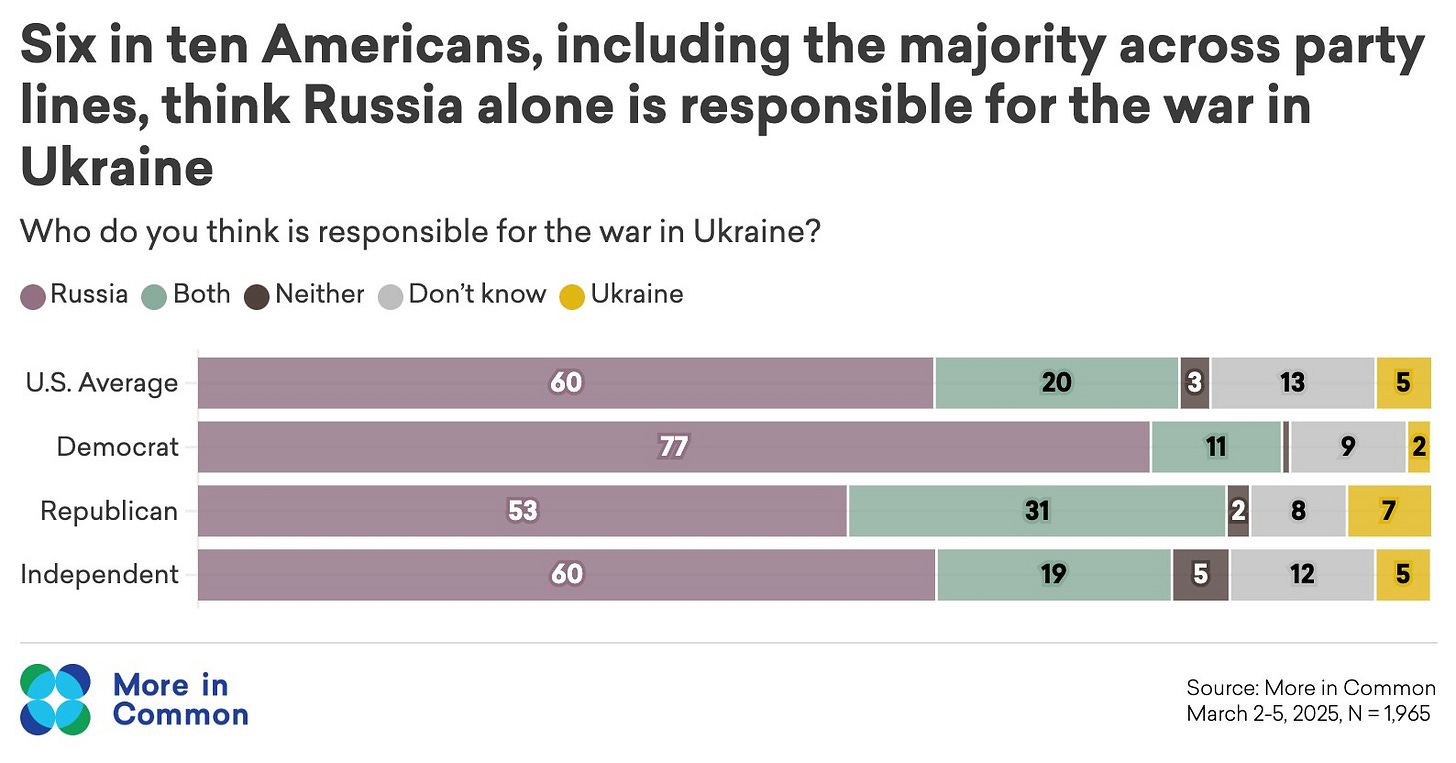

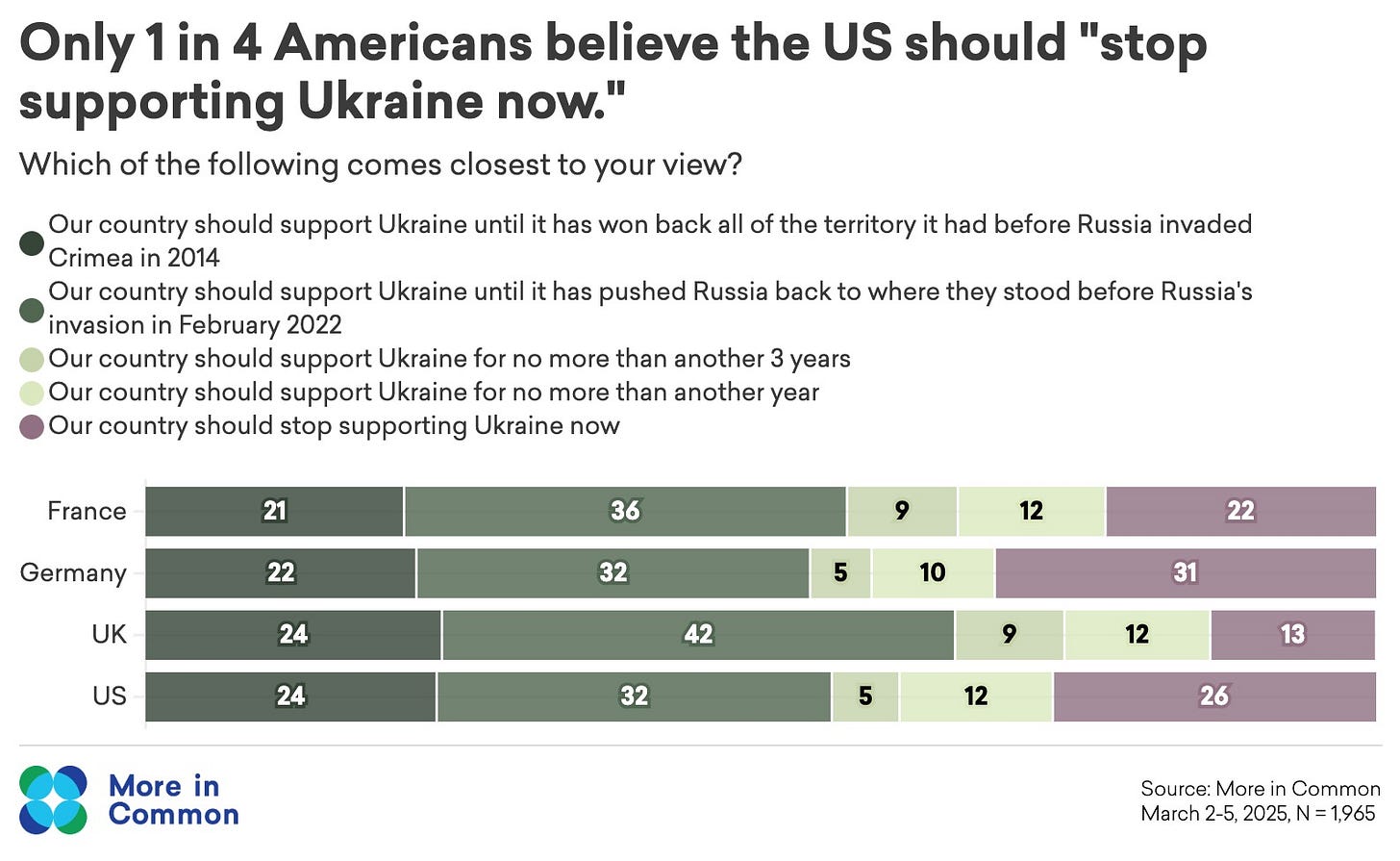

No matter how we asked the question, a majority of Americans, including a majority of Republicans: sympathizes with Ukraine more than Russia, thinks that Russia started the war, and thinks that the US should continue assisting Ukraine as it seeks peace. There are a number of questions we asked to assess American sentiment on these points, and I’ve shared a sample of those here. The purpose of showing the four charts below is to highlight that Americans are more aligned about the path forward with respect to Ukraine than the Oval Office meeting might have indicated.

Many Americans are Skeptical about the Costs of Global Leadership

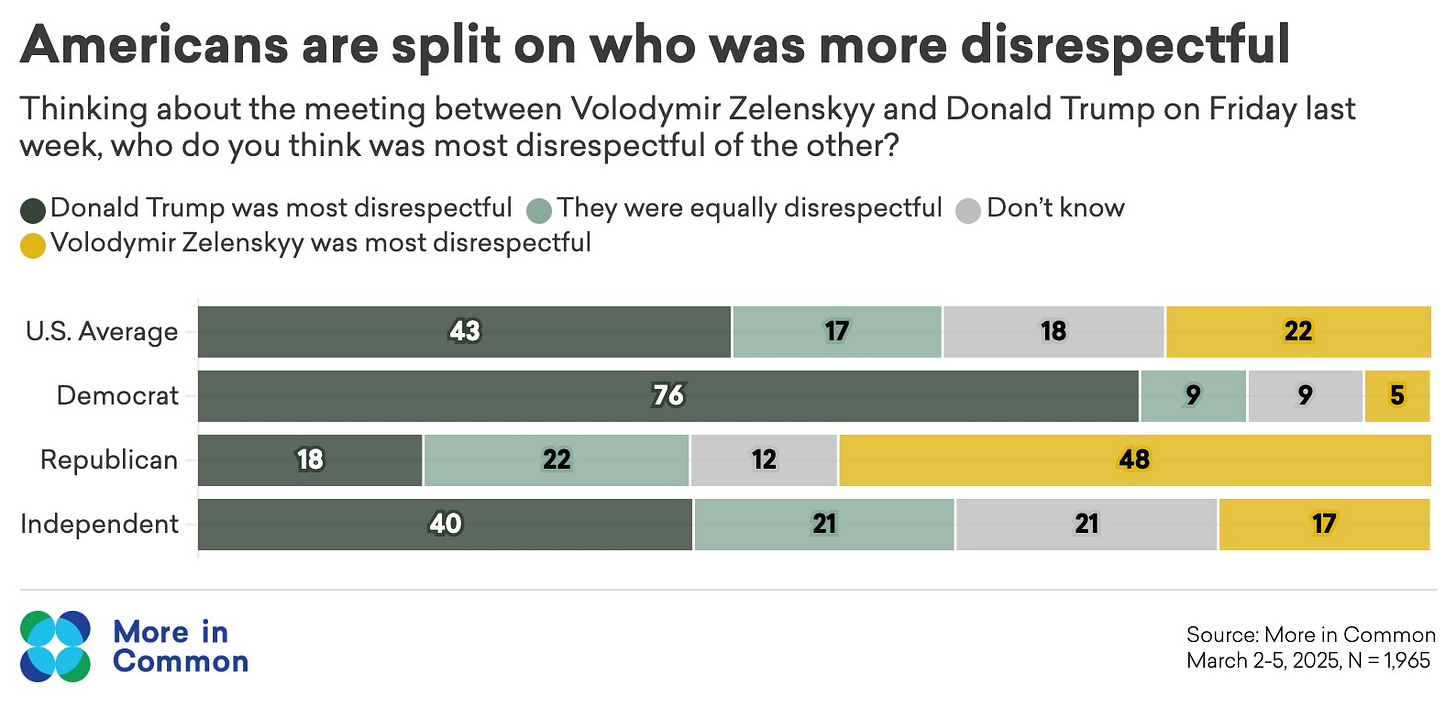

On the other hand, Americans substantively disagree along party lines about what happened in the meeting itself. Most Democrats felt that President Trump was most disrespectful in the meeting, whereas most Republicans felt that President Zelenskyy was most disrespectful.

It’s not a terribly surprising point: Republicans tend to like President Trump and Democrats tend to dislike him. The qualitative research points at the deeper meaning of this partisan schism.

Brandon, a 44-year-old Independent from Cincinnati said that he was “proud that Trump and Vance were willing to put optics aside and tell the truth about the situation. For too long Ukraine has taken money from the USA to further the NATO expansion agenda. The USA is done footing the bill for the rest of the World. If you want (or in this case need) our (the US taxpayers’) money, you do not get to lecture us on how much we give.”

Carrie, a 43-year-old Republican from Georgia said, “I felt like our President was doing his best to handle the situation and do what's best for America.”

Jennifer, a 47-year-old Republican from Georgia said she was “proud that our President and Vice President stood up for our country.”

There were plenty of Democrats, Independents, and even a handful of Republican panelists who were appalled at President Trump and Vice President Vance’s behavior in the Oval Office. I’m merely highlighting that, among those Americans who felt President Zelenskyy was most disrespectful in the Oval Office meeting—and our polling indicates that most Republicans feel this way—their sentiment seems to be wrapped up in some sense of pride in their president insisting that he won’t write blank checks.

This is even true for many respondents in our panel who think that the US should resist authoritarianism and stand up for democracy globally. As Liam, a 66-year-old Republican from Georgia put it, “I think we need to promote democracy but not at the expense of the US. Our country should come first.”

Getting a Good Deal

Americans, regardless of party, are proud that their country defends against authoritarianism. At the same time, a growing faction of Americans has earnest pride in leaders that stand up for our nation’s own parochial—and economic—interests.

Since the end of the Cold War—and certainly since September 11, 2001—political leaders could assume that voters saw overwhelming alignment between America’s role as a global leader and the country’s hard interests. At the very least, voters didn’t care enough about foreign policy to think about it in terms of trade-offs. If a president thought some foreign policy action was a good idea, he could usually just do it, unconstrained. There wasn’t just a Washington foreign policy consensus, but a national foreign policy consensus. To be sure, this led to some clearly good choices that we might not make today (providing humanitarian assistance to Haiti after the 2010 earthquake); and to some clearly bad choices that we might not make today (the Iraq War).

Trump’s leadership of American politics coincides with the chaotic early stages of reimagining American grand strategy in the post-Cold War, post-9/11 era. The struggle to define America’s role in the world is likely to continue until either a major foreign crisis forces clarity from the outside; or one party or another is able to secure a series of clear majoritarian victories, buying enough time to stably refashion American foreign policy in their vision. In the meantime, Democrats and Republicans alike will continue struggling over competing visions for America’s place in the world.

Whoever wins the midterms in 2026 or the White House in 2028, this debate will still be raging. In recent history, the players in this debate have been able to elide why American global leadership is so good for Americans. Whoever wins this debate won’t have that luxury. They’ll need to explain to Americans why their version of American global leadership is “a good deal.”

We can’t do this without you!

MIC regularly conducts research that sheds light on both cross-group misperceptions and common ground. Consider supporting our work by making a donation.